|

| A pilot and owner of a restored biplane, Larry Murdock now has set his sights on the waters below instead of the skies above. The entomology professor dreams of rafting the White, Wabash and Ohio rivers, to the mighty Mississippi, then going as far south as his homemade barge will take him. Photo by Tom Campbell |

By LARRY MURDOCK

I'm going to build a flatboat. A big, old-style, clumsy river flatboat like Midwestern farmers built five generations ago.

She'll be 12 feet wide and 20 feet long. I'll make her out of poplar or oak planks and peg her together like they did back then.

In fact, I am negotiating with my brother over a pile of oak, poplar and walnut beams he took out of a barn built in 1869 (our best guess). We are going to see if we can have them sawed into planks to use to build the boat.

She'll be the spittin' image of the homely, hand-hewn vessels that carried the bounty of Midwestern farms down the rivers to the markets in Louisiana in the 1850s. Our pioneer-farmer ancestors built such boats by the hundreds every year, from Missouri to Ohio to Kentucky and Minnesota.

It all started long before there were steamboats, steam trains and barge-pushing tugs. Pioneer farmers had to get their crops, livestock and manufactured goods to market one way or the other. The only way to do that in early times was to use the rivers. And all rivers west of the Alleghenies and east of the Rockies eventually led south to New Orleans.

Ocean-going sailing ships could reach New Orleans and carry cargos all over the world. And thus it was that our hardy pioneer ancestors, on the newly opened Midwestern land, came to trust their lives and their fortunes to crude boats built with rude tools by their own hands.

Their ungainly and crude cargo-hauling craft are long gone now. Even a hundred years ago they were already long gone, existing by then only as motes of memory floating in the heads of gray-haired old men.

The route is straightforward

I will build my boat on the banks of the West Fork of the White River in Greene County, Indiana, and launch her on the White and float her to the Wabash. Then we'll drift on down that half-forgotten stream to the Ohio, the beautiful river. I say "half-forgotten" because rivers aren't important anymore, leastways not one-tenth as important as they were in the old days.

If all goes well and our luck holds and we caulk our boat well with the right kind of oakum and we build her solid, my friends and I will trust her on to the Mississippi and let Old Man River himself carry us as far down as Natchez or New Orleans.

If we make it that far, I am determined to walk back to my starting point in Indiana. I know it sounds crazy, but that's what I said - I'm going to walk back.

Why? Because thousands of pioneers did it, and because the flatboat trip was marvelously interesting, yes, and a bit adventurous and a

little risky, though usually profitable, too, unless your boat's bottom was ripped out by a sawyer or robbers fell upon you in the night. In any case, the trip commonly ended with a walk back home, and I am jaw-set determined to find out what both the start and the finish of the trip were like.

A haunting, daunting plan

The whole thing is a little haunting, I admit, because all those people who made that weeks-long flatboat trip long ago, from the dawn days of Indiana to the 1870s - most of them obscure people at best, though Abraham Lincoln and Davy Crockett were experienced flatboaters - gave up the ghost a century or more ago. It's daunting too, because I don't know whether I can pull it off.

The honest truth is that I am a little worried, because I have no experience building boats and no proper plans for one because good plans for flatboats don't exist. If ever there were any in existence, they've long since been ground to bits by the mill of time.

Happily, there are a few fragments of drawings to go on, but little more than that. I know I'm going to have to rely on people who know a lot more than I do about building boats and navigating rivers. I've got to find those people and get their help.

Old-timer tells fascinating tale

My determination to do this goes back 26 years ago, when I heard a man named Clarence Dyar tell stories of flatboats - stories he had heard from a real-life flatboater. Dyar was married to a woman named Franklin and, thus, was my wife, Susie's, great uncle. Susie's paternal grandmother was a Franklin; a branch of their family came from North Carolina to Owen County, Indiana - 50 miles southwest of Indianapolis - in 1818.

At the time I talked to him, Clarence Dyar was about 85 or so. I met him at a Franklin family reunion in Worthington, Ind.

In the course of that hot, August afternoon family reunion, while the cicadas sawed and buzzed in the trees above us, Clarence talked about another family gathering, one he had attended as a little boy, around 1900. He said there was a very old man in attendance at that reunion, a man well into his 80s.

That old man fascinated young Clarence because he told stories about taking flatboats every spring from Freedom, Ind., down to New Orleans, boats he helped build with his own hands in the White River bottoms. They carried burdens of maple syrup, Indian corn and chickens or sawn lumber and hand-rived shingles and barrels of salted pork.

In New Orleans they sold their cargo, sold the boat, too, then walked back to Indiana.

He did this every year for 15 years, walking the entire 800 or 1,000 miles back home. He could have taken a steamboat, he said, but he wanted to save money because he was eager to buy land where he could build a house for a future wife and chop a farm out of the virgin Indiana timberland.

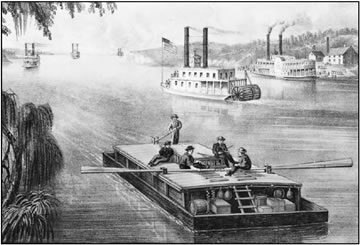

|

| Murdock's flatboat will resemble the one in this Currier and Ives illustration. Photo by Tom Campbell |

River profits went into land

Within days of trudging weary and footsore back into the yard of the homeplace, he would ride his mare down to Vincennes to purchase Congressional land, for which he paid $1.25 an acre. Scattered across every township in those days were numerous 40- and 80-acre tracts of land, just waiting to be claimed.

Thanks in part to year after year of adventures on flatboats, he eventually became a substantial landowner and wealthy, at least by the standards of the day. Some of the land is still in Susie's family.

That old flatboater was named Joshua Franklin. As it turns out, he was Susie's great-great-grandfather. We know precious little about him except a silly but true story. We know that on July 6, 1856, he was arrested and fined 50 cents for the high crime of fishing on Sunday! People took their religion real seriously back in those days - fishing on Sunday was a sin, and illegal to boot.

Many of us have stories like Joshua's in our family closet, but they have mostly been thrown out as useless trash, or just plain forgotten. Thanks to Clarence Dyar, Susie's flatboat heritage survives, at least these little tatters of it. I am personally grateful to Clarence, for nearly the same reason. He set off a slow-burning fireworks of a dream in my mind that continues to glow and smolder a quarter-century afterwards.

Clarence Dyar's story of Joshua Franklin brings to mind something else that we usually forget, namely that human memory has a long reach indeed. There I was, in 1980, talking to a guy who himself had talked to a man who had taken flatboats from Indiana to New Orleans in 1837.

Since that day in Worthington years ago, I've been pondering flatboats and the adventures and travails known by thousands of our forefathers. I've slowly come to recognize that there's a great untold story there, an experience that no longer lingers in any living human memory.

It needs to be unearthed (or maybe I should say pulled out of the murky waters into which it sank long ago) to let the sun shine on it and the fresh air blow over it. To be shared so others can see how marvelous and how undeserving to be forgotten it was.

It occurs to me that I must recreate that experience. I must live it. I'm not talking about merely imagining it and writing about it; it's much more than that.

I want to see what those flatboaters saw, to smell what they smelled and feel the wind on my face as they felt it - and that's why I'm going to build my flatboat one of these days.

It occurs to me that 25 years from now, when I go, God willing, myself an octogenarian, with Susie to attend a Franklin reunion down in Owen or Greene county, there'll be a boy there with curious eyes and an alert mind.

I'll tell him the story of Joshua Franklin, and maybe my own flatboat story, and then I'll hope he'll pass those stories on to some other kid, perhaps 75 years on.

Maybe, in that way, I'll pull an old chain of memories out of the river and pass it on.