Forensic expert and entomology alum, Neal Haskell, uses bugs to solve crimes

Indy Star

By Dan McFeely

November 26, 2007

|

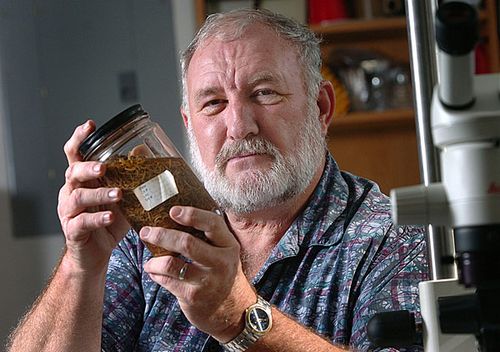

RECOGNIZED SKILLS: Neal Haskell, a world-renowned expert in the use of insects in police work, has been a witness in many trials and has inspired story lines on television shows such as "CSI" that rely on forensics. - STEVE HEALEY / The Star |

Neal Haskell

• Age: 61.

• Occupation: Board-certified forensic entomologist and professor at St. Joseph's College.

• Lives: On an 800-acre family ranch.

• Works: In his private forensic lab in the basement of his mom's home.

• Teaches: At St. Joe's and at special seminars for law enforcement and medical examiners across the country.

• Salary: Declined to say, but he is hired as a contractor by police, prosecutors, medical examiners and public defenders. Also is paid for teaching at St. Joe's, a private Catholic college.

• Born: Jasper County.

• Graduated: Rensselaer High School; Purdue University.

• Personal: Married; two kids.

• Favorite summer trip: Taking his then-16-year-old son Joel to the "Body Farm" in Knoxville, Tenn., for a few months of studying decomposing human bodies.

• Final destination: Has agreed to donate his own body to the Body Farm in Knoxville.

Blowflies and bodies

The most common kind of fly found buzzing around human remains is the blowfly, which is primarily blue or green and comes in different species.

• Blowflies seek out the warmest parts of the body and lay their eggs on the flesh.

• The resulting maggot will feed on the flesh before migrating away from the corpse to find a suitable spot for the pupal stage.

• Using scientific research on the evidence and comparing it with the known life cycle of blowflies, it's possible for forensic entomologists to determine how long a person has been dead.

• Time of death can be a crucial part of a murder investigation, helping to identify victims and rule out suspects.

• The type of blowfly found at a crime scene also can provide clues to where the body has been. For example, if blowflies known to live in warm, southern climates are found on a body discovered in a cold, northern region, there's a chance the body has been transported and then dumped.

Source: www.forensicentomology.com |

RENSSELAER, Ind. -- Every time FedEx shows up at the door, 91-year-old Buthene Haskell pretty much knows what's inside the package.

More bugs for her son, the globe-trotting "maggot man."

In an arrangement that would give most people the willies, Buthene lives in a small ranch house in this college town with her cat, Smoky -- and about 250,000 maggots and blowflies.

The bugs are kept in the basement, just off the laundry room. They're usually dead, pinned to a board or floating in a bottle.

This is where Neal Haskell does most of his research on insects. He is one of the few board-certified forensic entomologists in the country, an expert in studying the bugs found feasting on bodies at crime scenes. His skills can unlock mysteries such as when a person died or how far a body may have been moved after death.

"Every day is like Christmas to me," the 61-year-old scientist quips about the boxes of bugs that crime scene investigators ship him to analyze. "I never know what my day is going to bring."

A few blocks away, Haskell teaches the next generation of "CSI"-types at St. Joseph's College. And a few miles away, he lives on an 800-acre ranch that is littered with dead pigs, used to grow even more bugs for research.

But most of the time, you can find him at "Mom's house" working on the next big case for police departments, medical examiners and public defenders around the world.

In this small town, Neal Haskell is the real CSI guy, without the glamour of Las Vegas or the TV crime drama set there.

"I guess I am the real Gil Grissom," he jokes, referring to the show's main character, played by William Petersen.

Noted collection

For nearly two decades, Haskell has buzzed like his beloved blowflies around the world -- visiting crime scenes, doing field tests, offering expert testimony -- using creepy little bugs to help solve murder mysteries. By checking the stages of their development, Haskell can extract clues about, for example, the victim's time of death.

Not knowing whether the evidence will be needed again, Haskell keeps bugs from every case.

Those include the "Zoo Man" murders in Knoxville -- Tennessee's most expensive murder trial -- and the Danielle van Dam case, in which a 7-year-old girl was abducted and killed in San Diego. Haskell testified in both cases.

He also has served as an expert in the Steven Truscott case, a 1959 Canadian murder mystery that continues to capture attention after the initial conviction was overturned this year.

And then there are the bugs Haskell helped collect off the remains pulled from the blaze at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, where David Koresh and about 80 of his followers died.

"I should have put a few of those up on eBay," he joked recently over a hamburger at a pub in downtown Rensselaer.

Haskell is recognized as an expert witness and has been featured on Court TV, Discovery, The Learning Channel and other networks. And he was the inspiration for a number of story lines on "CSI" and its spinoffs.

Most of the time, it's jeans and a T-shirt for Haskell, an Indiana boy who grew up on the family farm and learned to love bugs in 4-H -- becoming fascinated with maggots when he stumbled upon dead animals at the ranch.

"I never dreamed that 35 years later I'd be deeply engaged in using maggots to solve murder," he recalled. "Maggots are beautiful."

And as any "CSI" fan knows, they can tell stories.

The kinds of stories that solve crimes and send murderers to Death Row.

Bugs tell time

Forensic entomology is the study of bugs found at the scene of a crime to determine how long a victim has been dead. Whether the bugs are buzzing around bodies, laying eggs or found in the pupal stage as they develop from maggot to blowfly can be crucial evidence.

And comparing the age of the fly with its species -- there are urban and rural flies, northern and southern, East Coast and West Coast -- one also can learn where a victim was killed and how far the body was transported before being dumped.

For years, such evidence was ignored, washed away on the autopsy table while investigators focused on rigor mortis and stomach contents to determine the time of death.

"When I was working homicide cases back in the 1970s, I noticed that bugs were usually present on victim's bodies found outdoors," said Joe Bono, recently retired director of the Secret Service Laboratory in Washington, who now serves as an adjunct instructor in forensic and investigative sciences at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. "In those days, we thought little about associating the time of death with the type or amount of infestation."

These days, every insect, maggot and pupa is collected with nets and jars and preserved for scientific inspection. Because bug evidence is affected by the weather and other conditions -- Was the body wrapped in a blanket? Sealed in a drum? Buried? -- investigators often use dead pigs kept in similar conditions to grow evidence to compare with that collected at the crime scene.

Haskell's farm is littered with the pig carcasses, which attract the same bugs drawn to humans. He often brings students to the farm as part of their training.

"You can't beat experience," Haskell said. "You can't beat taking bugs off a dead pig."

After receiving a bachelor's degree in entomology at Purdue University, Haskell tried to make a living on his family farm while serving as a special deputy for the Jasper County Sheriff's Department. When farming began to go downhill in the 1980s, he decided to return to school and go for a master's degree in entomology.

Looking for a way to make his love of bugs pay the bills, he decided to couple that with a second master's degree in forensics. That's a rare combination. There are only 13 board-certified experts in America, according to www.forensicentomology.com, a Web site maintained by Dr. Jason Byrd of the University of Florida.

Haskell estimates he has worked on more than 800 criminal cases. His work has helped convict murderers and send many to Death Row.

Murder down under

Back at Mom's basement, Haskell shows a visitor some of the rare living bugs inside what he calls a "maggot motel."

In these small containers, Haskell grows maggots in specific conditions to compare with others found at a crime scene. The best results come in specimens given enough time to develop.

Depending on the type of blowfly, it can take as little as 15 days to grow a maggot in constant 80-degree temperatures.

The current maggot motel was created at the request of the Quincy (Ill.) Police Department, which is investigating a body found inside a closet at an abandoned home.

Nearby on the same table, another controlled experiment is taking place inside an old Graeter's pint ice cream container.

"That is for blowflies that like it a little cooler," joked Haskell, who spends more time in the lab than in court. He is called to testify about a dozen times a year.

A few years ago, the sister of a man convicted of murdering his wife and two daughters in Australia hired him to investigate and possibly clear her brother's name. With the help of his St. Joe students -- who made several trips to Australia to monitor dead pigs and bring back bug evidence -- Haskell has collected about 75,000 specimens, and the case is ongoing.

It's an exciting life when you get phone calls from detectives and medical examiners around the world to help solve crimes.

"We've used Dr. Haskell several times here," said Lt. Chris Jones, who works in the CSI section of the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department. "He has trained our people on insect analysis and collection for evidence, and we've sent folks to his school in Indiana for training."

At St. Joseph's, where his son also teaches as an adjunct professor in forensics, students know that when Haskell talks about plucking bugs from a body, he is speaking from experience.

Haskell has been on the faculty at St. Joe's full time since 1997. While the private Catholic college does not offer a forensic entomology program, Haskell said it provides a solid foundation for students to spring into that field and land in some good jobs.

Over time, he has become immune to much of what would make most people gag.

"It's damn disgusting," Haskell admits. "Dirty, smelly. The stuff we work with, the things we see; the horrible things we human beings do to each other. It's not fun stuff."

And it's hard to forget.

The worst was when he was called to a muddy Indiana field where the bodies of a mom and her two kids were unearthed.

He can still see the face of the little girl with a bullet hole in her forehead, an image that gave him nightmares for five years.

"I don't know what it was. I guess my kids had once been that age. And it just got to me," Haskell said. "I had real trouble sleeping after that."

|